Andreas_Kreuz

Human

- Joined

- Sep 13, 2023

- Posts

- 447

The thread self-editing-for-authors collects aspects and techniques to check when you edit your stories. However, as an occasional editor, I have noticed that fine-grained editing (sentences, spelling, punctuation) is sometimes too early, because the coarse grained architecture was broken.

I have edited stories that were written well (Good language, natural dialogues, precise visceral descriptions, etc.) but where the fundamental structure just did not align.

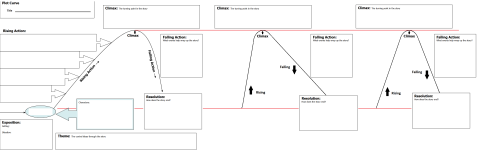

I believe before that, as authors, we need to get the story architecture right first. With this, I mean that before detailed editing, we need to check some coarse-grained fundamentals like:

- A narrative arc that is coherent and has no gaps.

- Verisimilitude - requiring that even a completely fantastical world or scenario has to follow inherent rules and logic.

- Plausibility - is the plot and the behaviours of the characters plausible and doesn't jump.

- Closure - does the story lead somewhere?

What further aspects do you expect a story to follow, and how do you check for them?

Maybe we can compile a similar list here.

I have edited stories that were written well (Good language, natural dialogues, precise visceral descriptions, etc.) but where the fundamental structure just did not align.

I believe before that, as authors, we need to get the story architecture right first. With this, I mean that before detailed editing, we need to check some coarse-grained fundamentals like:

- A narrative arc that is coherent and has no gaps.

- Verisimilitude - requiring that even a completely fantastical world or scenario has to follow inherent rules and logic.

- Plausibility - is the plot and the behaviours of the characters plausible and doesn't jump.

- Closure - does the story lead somewhere?

What further aspects do you expect a story to follow, and how do you check for them?

Maybe we can compile a similar list here.